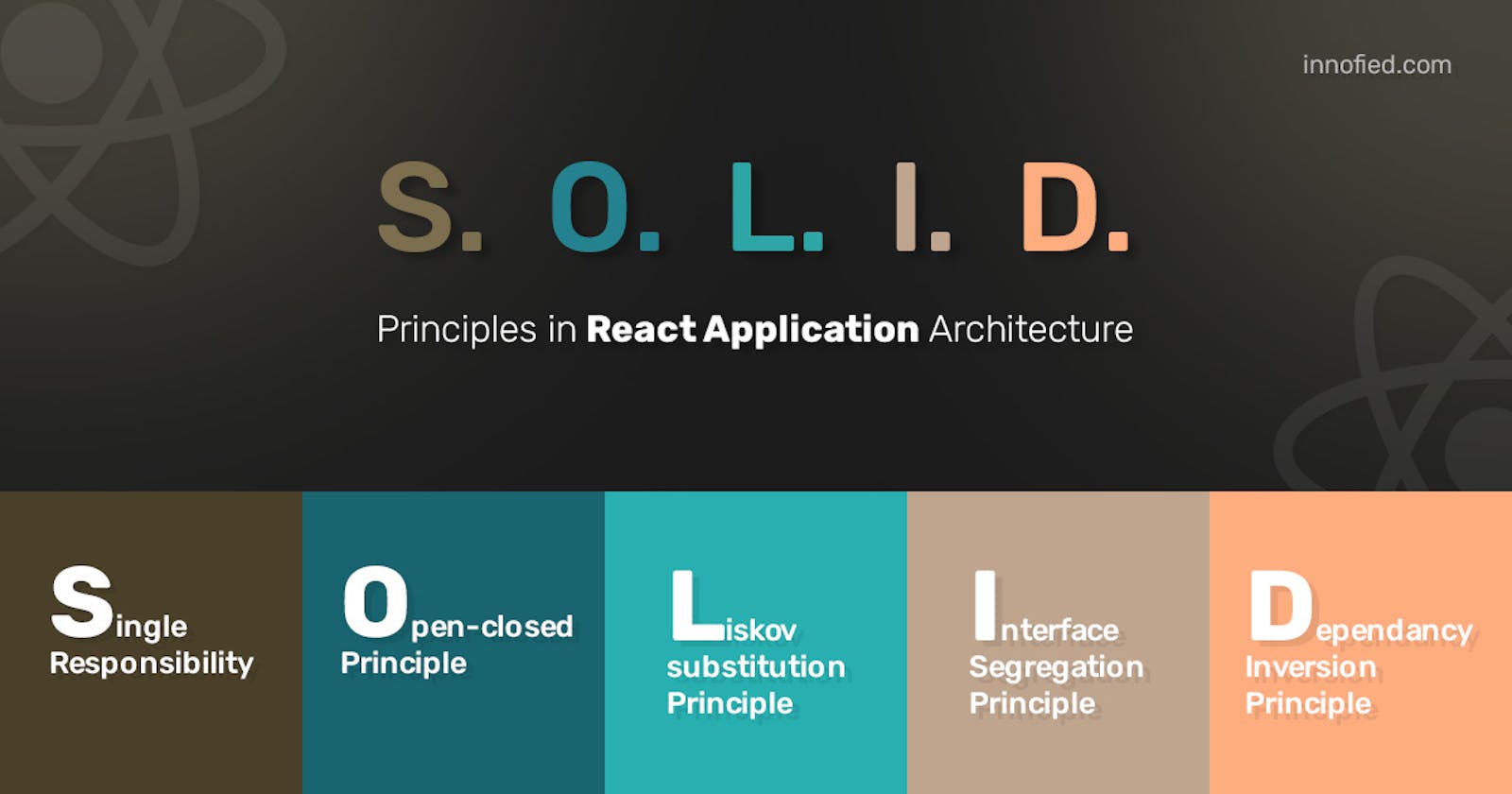

SOLID is an acronym that stands for the first five OOD principles as outlined by renowned software engineer Robert C. Martin. The SOLID principles are designed to help developers design robust, maintainable applications.

The five SOLID principles are:

Single-responsibility principle

Open–closed principle

Liskov substitution principle

Interface segregation principle

Dependency inversion principle

Single-responsibility principle

- The single responsibility principle says that a class or module should have only a single purpose

/*

Below is the example which violates the single responsibility principle because it's uses two methods inside one class

and both methods have different purposes

*/

class CalorieTracker {

constructor(maxCalories) {

this.calories = 0;

this.maxCalories = maxCalories;

}

trackCalories(calorieCount) {

this.calories += calorieCount;

if (this.calories > calorieCount) {

this.errorLog("maximum calories exceeded");

}

}

errorLog(message) {

console.warn(message);

}

}

const calorieTracker = new CalorieTracker(1500);

calorieTracker.trackCalories(500);

calorieTracker.trackCalories(1200);

// Solution

/*

now both ErrorLog and CalorieTracker classes have different purposes

*/

class ErrorLog {

warn(message) {

console.warn(message);

}

}

class CalorieTracker {

constructor(maxCalories) {

this.calories = 0;

this.maxCalories = maxCalories;

}

trackCalories(calorieCount) {

this.calories += calorieCount;

if (this.calories > calorieCount) {

ErrorLog.warn("maximum calories exceeded");

}

}

}

const calorieTracker = new CalorieTracker(1500);

calorieTracker.trackCalories(500);

calorieTracker.trackCalories(1200);

Open–closed principle

- The open-closed principle says that code should be open for extension, but closed for modification

What this means is that if we want to add additional functionality, we should be able to do so simply by extending the original functionality, without the need to modify it

/*

Below is the example which violates the open-closed principle because in order to make below example work

we are modifying original class.

*/

class Vehicle {

constructor(fuelCapacity, fuelEfficiency) {

this.fuelCapacity = fuelCapacity;

this.fuelEfficiency = fuelEfficiency;

}

getRange() {

let range = this.fuelCapacity * this.fuelEfficiency;

if (this instanceof HybridVehicle) {

range += this.electricRange;

}

return range;

}

}

class HybridVehicle extends Vehicle {

constructor(fuelCapacity, fuelEfficiency, electricRange) {

super(fuelCapacity, fuelEfficiency);

this.electricRange = electricRange;

}

}

const standardVehicle = new Vehicle(25, 50);

const hybridVehicle = new HybridVehicle(30, 40, 50);

console.log(standardVehicle.getRange(), hybridVehicle.getRange());

// Solution //

class Vehicle {

constructor(fuelCapacity, fuelEfficiency) {

this.fuelCapacity = fuelCapacity;

this.fuelEfficiency = fuelEfficiency;

}

getRange() {

return this.fuelCapacity * this.fuelEfficiency;

}

}

class HybridVehicle extends Vehicle {

constructor(fuelCapacity, fuelEfficiency, electricRange) {

super(fuelCapacity, fuelEfficiency);

this.electricRange = electricRange;

}

getRange() {

return this.fuelCapacity * this.fuelEfficiency + this.electricRange;

}

}

const standardVehicle = new Vehicle(25, 50);

const hybridVehicle = new HybridVehicle(30, 40, 50);

console.log(standardVehicle.getRange(), hybridVehicle.getRange());

Liskov substitution principle

- Liskov Substitution Principle (LSP) states that objects of a superclass should be replaceable with objects of its subclasses without breaking the application. In other words, what we want is to have the objects of our subclasses behaving the same way as the objects of our superclass

class Bird {

fly() {

console.log("can fly");

}

}

class Eagle extends Bird {

dive() {

console.log("can dive");

}

}

class Penguin extends Bird() {

// Problem: Can't fly!

}

// Solution //

class Bird {

layEgg() {}

}

class FlyingBird {

fly() {

console.log("can fly");

}

}

class SwimmingBird extends Bird {

swim() {

console.log("can swim");

}

}

class Eagle extends FlyingBird {}

class Penguin extends SwimmingBird {}

Interface segregation principle

- The Interface Segregation Principle states that a client should never be forced to implement an interface that it does not use, or clients shouldn't be forced to depend on methods they do not use

/*

Imagine we have a streaming platform that has two types of users, a FreeUser and a PremiumUser, both extending from User

*/

class User {

constructor(username) {

this.username = username;

}

skipAd() {

console.log(`I'm going to skip if I'm premium`);

}

startParty() {

console.log(`I'm going to start a party if I'm premium`);

}

}

class FreeUser extends User {

constructor(username) {

super(username);

}

skipAd() {

return null;

}

startParty() {

return null;

}

}

class PremiumUser extends User {

constructor(username) {

super(username);

}

skipAd() {

console.log(`Ad was skipped.`);

}

startParty() {

console.log("Party started, invite your friends!");

}

}

// The following code will execute

// and print the message

const premium = new PremiumUser("premium_username");

premium.skipAd();

premium.startParty();

// The following code will execute

// but return null

const free = new FreeUser("free_username");

free.skipAd();

free.startParty();

/*

Taking into consideration that only a PremiumUser is able to skip ads and start parties, we are violating the Interface Segregation Prinicple by forcing both User and FreeUser to implement these actions. To apply the principle, we may use composition to only give these functionalities to PremiumUser. After applying the principle, the code would be the following

*/

class User {

constructor(username) {

this.username = username;

}

}

class FreeUser extends User {

constructor(username) {

super(username);

}

}

class PremiumUser extends User {

constructor(username) {

super(username);

}

}

const premiumBenefits = {

skipAd() {

console.log('Ad was skipped.');

},

startParty() {

console.log('Party started, invite your friends!');

},

};

Object.assign(PremiumUser.prototype, premiumBenefits);

// The following code will execute

// and print the message

const premium = new PremiumUser('premium_username');

premium.skipAd();

premium.startParty();

// The following code will throw an exception

// because a FreeUser does not implement these methods

const free = new FreeUser('free_username');

free.skipAd();

free.startParty();

Dependency inversion principle

The dependency injection principle states that high-level code should never depend on low-level interfaces, and should instead use abstractions

/* Let’s say we have a piece of software that runs an online store, and within that software one of the classes (PurchaseHandler) handles the final purchase. This class is capable of charging the user’s credit card, and does so by using a PayPal API: */ class PurchaseHandler { processPayment(paymentDetails, amount) { // Complicated, PayPal specific logic goes here const paymentSuccess = PayPal.requestPayment(paymentDetails, amount); if (paymentSuccess) { // Do something return true; } // Do something return false; } } /* The problem here is that if we change from PayPal to Square (another payment processor) in 6 months time, this code breaks. We need to go back and swap out our PayPal API calls for Square API calls. But in addition, what if the Square API wants different types of data? Or perhaps it wants us to “stage” a payment first, and then to process it once staging has completed? That’s bad, and so we need to abstract the functionality out instead. Rather than directly call the PayPal API from our payment page, we’ll instead create another class called PaymentHandler. The interface for this class will remain the same no matter what underlying payment system we use, even if the two systems are completely different. We’ll still need to make changes to the PaymentHandler interface if we change payment processor, but our higher level interface remains unchanged */ class PurchaseHandler { processPayment(paymentDetails, amount) { const paymentSuccess = PaymentHandler.requestPayment( paymentDetails, amount ); if (paymentSuccess) { // Do something return true; } // Do something return false; } } class PaymentHandler { requestPayment(paymentDetails, amount) { // Complicated, PayPal specific logic goes here return PayPal.requestPayment(paymentDetails, amount); } }